Flora & Pharma

Medicinal Plants and Pandemic Attire

Becka Rahn, Resident Artist Research Project showcase artist

Becka Rahn dives into our Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas for an arts showcase project drawing on the collection of the University of Minnesota Herbarium at the Bell Museum. Rahn, a fabric designer and fiber artist, selected 25 medicinal plant species from the collection. She created cut paper illustrations, digitally printed those onto fabric, and then sewed the fabric into cotton masks. The project includes activities, too! You can fold your own origami bunchberry leaves, make a mobile, download coloring pages, and more.

Find the full set of masks, videos showing Rahn’s process, and more activities at Rahn’s website

Here, Becka Rahn and Timothy Whitfeld, Herbarium Collections Manager, comment on a few of the species Becka chose for her project. This part of Rahn’s project will be on view in the Dr. Roger E. Anderson Education Wing.

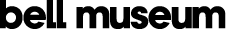

Round-Leaved Sundew

Drosera rotundifolia

Sundews grow in low-nutrient boggy or sandy habitats. They are found across the forested parts of Minnesota, and in northern latitudes around the globe. But round-leaved sundew is not just a circumboreal species; there are outlier populations in high alpine zones in the mountains of New Guinea, in the South Pacific.

What I find fascinating about sundews is their strategy for finding nutrients in the harsh environments where they grow. They are carnivores, and they trap small insects on globules of sticky fluid on their leaves. That fluid contains proteolytic enzymes that break down animal protein, providing the plant with nutrients.

– Tim

MIN435525

One of the things I liked most about making this mask was that sundew leaves are so unusual. If I asked you to draw a leaf, you would probably draw something green and droplet shaped, but sundew leaves don’t look like that at all. Sundews have round leaves that look like a sparkly red and green starburst, and they use them to trap insects.

On many plants, the flower is the showiest part of the plant. Though sundew has pretty little flowers, the leaves are really the most interesting part.

I also like that even though they are boldly colored, they are really tiny. The sundew art I made is like a zoomed-in view. The plant itself is only a few inches high and a single leaf is only about the size of the tip of your pinky finger.

– Becka

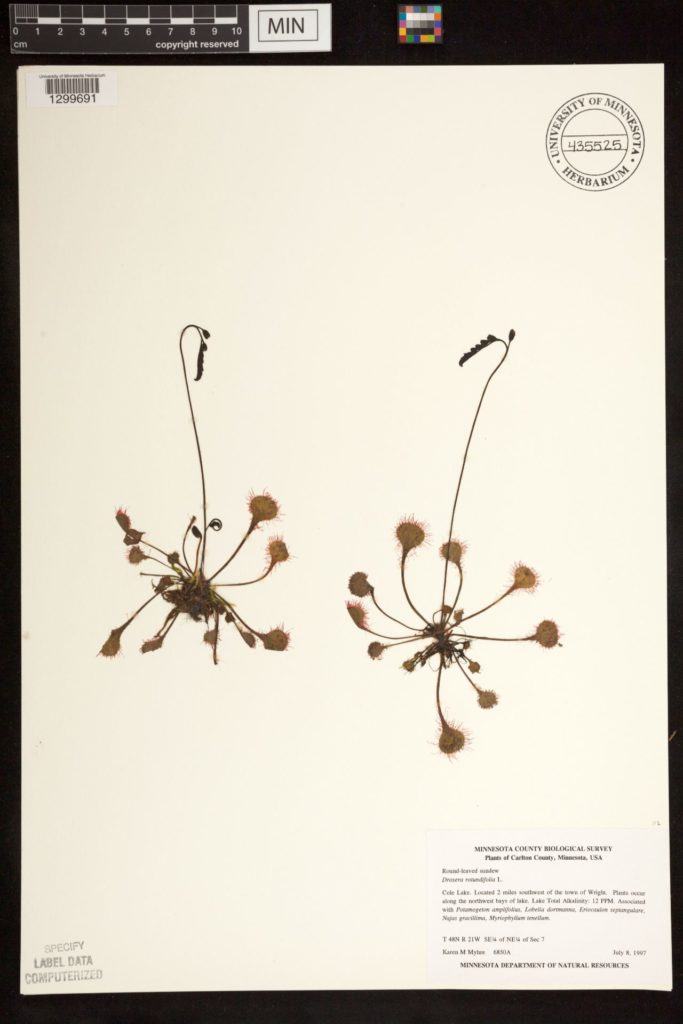

Bunchberry (Dwarf Dogwood)

Cornus canadensis

One of the things about the bunchberry that jumped out at me right away is how symmetrical it is. All of the leaves and bracts are in pairs and they form a very precise pattern. If you see a photo of a field of bunchberries, they almost look like a geometric pattern repeating over and over.

As an artist, I think about how humans make repeating patterns all the time: think of brick walls, checker boards, or the way you line up your office supplies in rainbow order. I think it’s really neat when we can find patterns in nature that just happen on their own.

– Becka

MIN781347

Unlike its relatives, which are mostly shrubs, this species of dogwood creeps along the ground, forming mats of glossy green foliage. It is relatively common in moist forests and boggy habitats in Minnesota. It spreads pollen by catapulting grains into the air at high speed, thanks to a release of elastic energy stored in its anthers.

What drew me to this species was what I thought were large showy flowers. But I was fooled!! What appears to be a single large white-petaled flower is really a cluster of tiny cream colored flowers surrounded by four white modified leaves called bracts. Late in the season, these small flowers produce a cluster of shiny red fruits.

– Tim

Large-Flowered Trillium

Trillium grandiflorum

This is the largest-flowered of Minnesota’s trilliums. Its showy white flowers change to purple as they age. These flowers are a treat in the spring, and I’ve seen continuous carpets across the forest floor. I also find it fascinating that trillium seeds are mostly dispersed by ants, so they don’t travel very far!

Like other spring-flowering species, trilliums are threatened by grazing white-tailed deer, and by invasive earthworms which decimate the organic “duff” layer where seedlings of many forest species germinate and establish.

Large-flowered trillium has been reported to have antifungal properties and novel steroidal saponins have been isolated from other trillium species, many of which have shown potential for cancer treatments. The general decrease in abundance of forest wildflowers represents a loss of other potential medicinal species such as bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) and Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum biflorum).

– Tim

MIN708749

Trilliums are also common in forests in upstate New York where my parents grew up. The last time my mom went to visit family there, she texted me a video of a huge carpet of trillium in the woods, with all of the plants rippling in the breeze. They were one of her favorite flowers to look for as a kid because they were easy to spot with their distinctive petals in groups of three.

The hardest part of making the trillium art was trying to capture the soft ruffles at the edges of the flower petals and then convey that in a flat plane.

– Becka

Pipsissewa (Noble Prince’s-Pine)

Chimaphila umbellata

The pipsissewa was the very first plant illustration I created for this collection of art. When I was making my list of plant species, I loved the name pipsissewa though I had never seen one before. Now I really want to find one in the wild so I can see it in person!

The word “umbellata” in the scientific name means umbrella; I think the flowers do look like fanciful umbrellas from a fairytale forest. Pipsissewa was one of the most brightly colored of all the native species I chose to illustrate, with the hot pink crown shape on its flower contrasting with the bright green cap.

– Becka

MIN166613

I have been lucky enough to see this evergreen groundcover growing in Minnesota’s forested habitats. It’s beautiful!

This particular specimen was collected in 1883 from Mount Pleasant, MN (Wabasha County) by Sara Manning. Manning was an expert in Minnesota’s botany, despite the limitations placed on her as a woman of her time.

Manning’s family moved to the Minnesota Territory in 1856; she later studied at Carleton College. An outdoor enthusiast, she documented plants during excursions around the state and compiled one of the earliest lists of Minnesota’s flowering plants. When she died at just 47 years old, she was already an honorary life member of the Minnesota Horticultural Society, as well as a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

– Tim

Artist’s statement

In 2019, I was chosen to participate in the Bell Museum’s Resident Artist Research Project. By 2020, being a “resident artist” had a new definition. As we moved to distanced and virtual experiences, I struggled to find a way to connect my art to the collections and community of the Bell Museum. At the same time, the pandemic meant that my sewing skills were suddenly in high demand by an entirely different community.

Early on, when masks and supplies were hard to get, it was inspiring to see the creativity that came from the need for masks. Every week I would find a new design or pattern that another stitcher had created for better or function. That creativity wasn’t about making masks pretty, but about the careful engineering involved in transforming something soft and flexible into a specific three-dimensional shape. I read articles about the filtering properties of different fabrics and looked at microscopic photos of fiber structures. Scientists studied the electrostatic properties of different fabrics and learned how each filtered particles. Making masks was a real fusion of art and science: the handcraft of sewing combined with the physics of fibers.

Thinking about this fusion made me wonder about other fields of science that could be studying the pandemic: not just epidemiologists and materials engineers, but also scientists who study plants. Some have been researching plant fibers, like the cotton used for making masks at home; others study the medicinal qualities of plants for treating illnesses. Medicinal plants grow in Minnesota and are represented in the collection of the University of Minnesota Herbarium at the Bell Museum.

Studying the Bell Museum’s digital herbarium collection and field guides of Minnesota plants, I chose 25 native species and created a cut paper illustration of each to be featured on a cotton mask. I made the illustrations from paper, also made from plant fibers, and digitally printed them onto organic cotton fabric using eco-friendly inks. I sewed each mask using a pattern I adapted from those that circulated throughout 2020. In keeping with the need for a virtual experience, I photographed the collection in my studio and created a virtual exhibition that you can explore from anywhere. I also created a collection of videos and activities to provide other ways to interact with the art.

A small selection of my masks will be on display at the Bell this spring. Afterward, I will donate all of the masks I made for this project to local art and science teachers. I hope to support them, and to inspire their students to look at the intersections of art and science in new ways.

-

Echinacea Angustifolia Coloring Pages

Color your own purple coneflower (Echinacea angustifolia) designChoose either a full-page illustration or a half-page notecard so you can send a note to someone to say hello. Each design fits on regular letter-size paper. Just download the .pdf and print on heavy-weight paper from your own printer.

-

Origami Bunchberry Tutorial

Learn to fold origami bunchberry leaves with this videoLearn to fold your own bunchberry (Cornus canadensis ) leaves from rectangles of paper in this video origami tutorial. You just need a few rectangles of green paper, like wrapping paper, tissue paper, or origami paper.

-

Marsh Marigolds Cut Paper Pattern

Download, paint and make your own cut paper marsh marigolds (Caltha palustris).Print this page on heavyweight letter-sized paper on your printer, add color with paints, colored pencils, or pastels and then cut out and assemble your own cut paper scene.