Predicting the Future With Plants

Get to know George Weiblen, the Bell’s science director and curator of plants.

Published01/22/2020 , by Eve Daniels

What do a rare coconut from the Seychelles and a 100-year-old wildflower from Minnesota have in common? This might sound like the setup to a bad botany joke, but there’s a serious connection between them. Found on only two islands in the world, the endangered double coconut is currently threatened by sea level rise and habitat loss. The wildflower, a rue anemone, is still abundant in Minnesota, but today it blooms an average of two weeks earlier than it did a century ago.

Both species offer strong evidence for a warming climate and its impact on plant life. They are also both part of the Bell Museum’s plant collection.

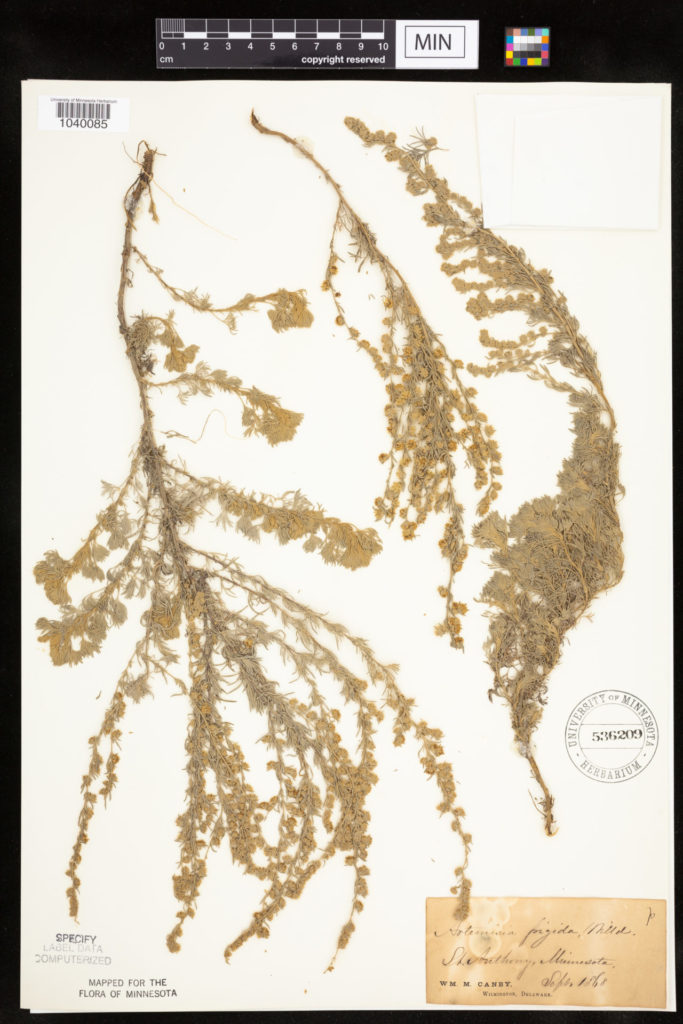

The collection holds about 900,000 specimens, dating back to the late 18th century. This includes vascular plants, bryophytes, algae, lichens, and fungi—labeled with who, what, when, why, and how they were collected—alongside each specimen. The objects are pressed, dried, and preserved as part of an ever-expanding herbarium.

George Weiblen, Bell Museum science director, curator of plants, and a Distinguished McKnight University Professor in the College of Biological Sciences, says the collection supports a wide range of activities.

“This includes naming new plants, teaching students about biodiversity, and studying how species adapt to changing environments. It also serves as a tool for identifying endangered species, exotic invasive species, and poisonous organisms that pose risks to humans and their pets.”

Growing up in Minneapolis, Weiblen often accompanied his father on field research trips. His dad was a geologist who studied rocks in Northern Minnesota, giving his son an early appreciation of the natural world. Years later, Weiblen earned his doctoral degree in evolutionary biology from Harvard, focusing on fig trees in Papua New Guinea.

He says serendipity brought him back to Minnesota. “Being situated at the Bell Museum is central to everything I do as a botanist, but my research is about as far away from Minnesota as you can get.”

A prairie sagewort specimen from the Bell Museum, collected in 1868 by W. Canby from Hennepin County, Minnesota.

In the past 25 years, he’s been to Papua New Guinea at least two dozen times. In 1997, Weiblen co-founded the Binatang Research Center near Madang. Since then, he and a team of citizen scientists have identified at least 250,000 trees and more than 500 species, culminating in the publication of a handbook of traditional knowledge and biodiversity.

The Bell’s plant collection holds specimens from Weiblen’s global research, including original collections of new species, which are essentially the birth certificates for scientific names.

“The world is more interconnected than ever, and many of the challenges that people are facing in a faraway place like New Guinea are shared with us in Minnesota,” he says. “How do we live within our limits and how do we adapt to change? These are common challenges and comparing the extremes may provide insight for the future.”

Grassroots Research

A big goal of the new Bell Museum is to boost public engagement with the scientific collections. Curators partner with citizen scientists through Mapping Change, an online project that aims to capture data from the collections for studying how animals, plants, and fungi change over time.

This work feeds data to the Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas. The atlas currently holds about 800,000 records, with plans to expand to 1.6 million records over the next three years, with support from Minnesota’s Environment & Natural Resources Trust Fund.

Thanks in large part to the Minnesota Biological Survey, the Bell has one of the country’s most comprehensive records of how plants are distributed across the state, along with an historic collection of flora from the Upper Midwest. This includes specimens from the expedition of French explorer Joseph Nicollet, when he visited the rivers of Minnesota in the 1830s.

“In order to predict where species will be in the future, we need to know where they’ve been in the past,” Weiblen says. “But these questions are too big for scientists to answer alone—we need everyone’s help.