Touch & See Lab at 50

The first hands-on natural history discovery room is still enchanting visitors.

Published11/30/2018 , by Meleah Maynard

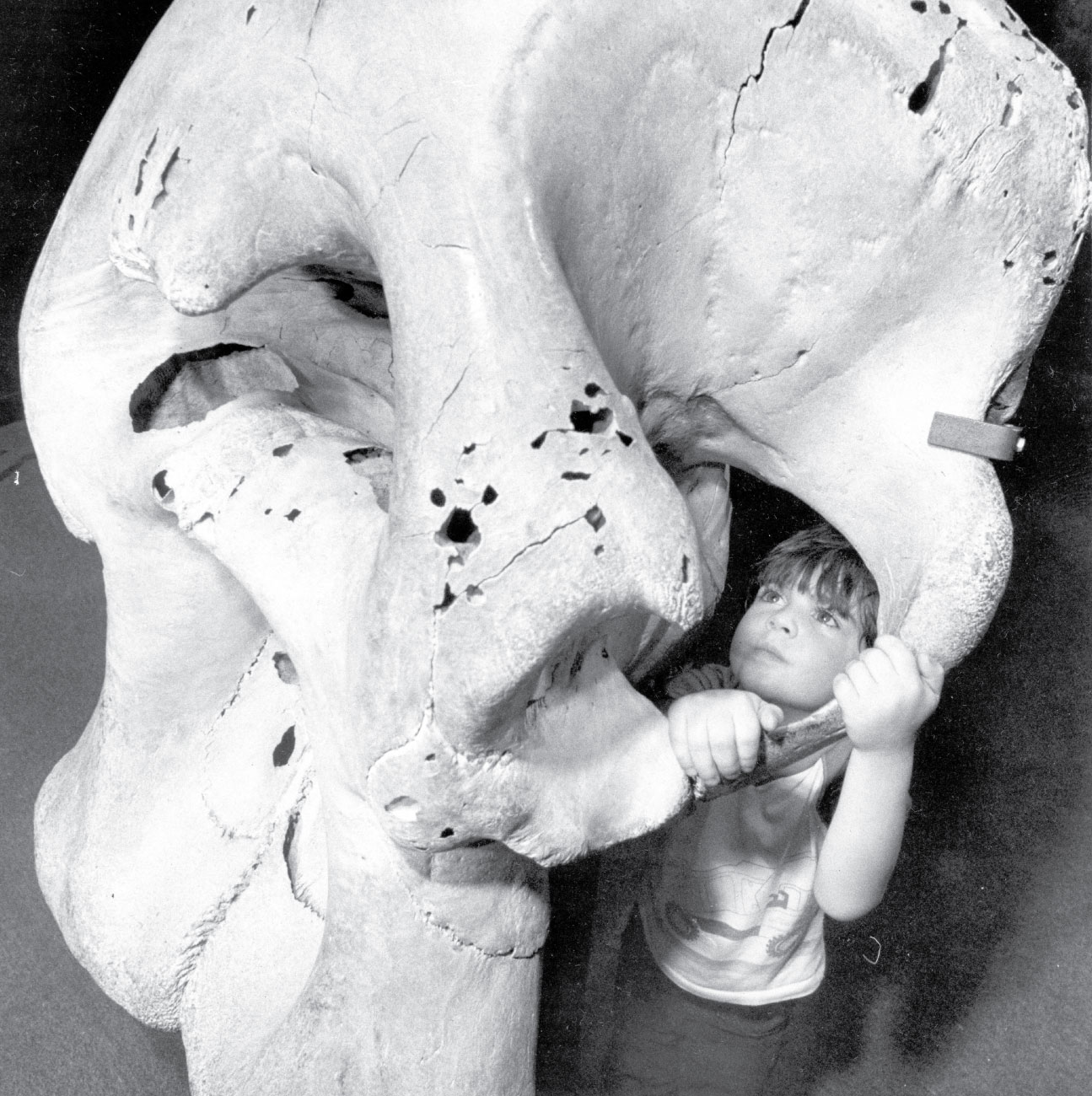

In the 1960s, natural history museums were understood to be somber places where people looked at things that were kept behind glass. But Richard “Bart” Barthelemy didn’t much like that idea. Working as the Bell Museum’s public education coordinator at the time, he’d seen clearly how much people yearned for a more interactive experience, especially children who, though they made up about 75 percent of the museum’s visitors, had a poor view of the mostly adult-height exhibits.

So, though it was unheard of at the time, Barthelemy headed to the Bell’s basement and pulled a few items from the museum’s collections. Back upstairs, he spread everything out on a blanket and invited people to sit down with him for a hands-on learning experience, believing that it was okay if skulls lost a few teeth and furs were rubbed bare by curious fingers. Everyone loved it, especially kids, so he teamed up with Roger Johnson, a professor with the University of Minnesota’s College of Education and Human Development, to create a proposal for what became the Touch & See Room. Opened in 1968, it was the first room of its kind at any natural history museum in the country.

Touch & See founder Richard Barthelemy (1916-1988) with young students in the 1970s.

Fifty years later, the renamed Touch & See Lab is now open in its new spacious, airy home in St. Paul. But while it has modernized a bit, Barthelemy’s daughter, Ann, believes her dad would be proud of the way the room remains rooted in its original mission. “He would love how it continues to encourage hands-on exploration and discovery without the intervention of a lot of technology,” she says, explaining that though Barthelemy was fascinated by the idea of computers, he believed strongly in exploring nature with your hands and eyes. “He loved nature and learning, and he brought all of that enthusiasm home too,” she says. “It’s really nice that the museum continuees to honor his efforts and life dream.”

Johnson still remembers how Barthelemy came to his office, asking: “As someone from child development, what sorts of things would you do to make things interesting and fun?” Working together, they convinced administrators that: “The Touch and See Room is not a place where you read plaques and just stand and look,” Johnson recalls. “It’s a place where you interact and ask questions because that’s much more interesting to kids and adults. I remember asking kids to pull out different specimen drawers and put their hands inside to see if they could tell what they were feeling. They were uneasy about doing it at first, but once they did it, they thought it was great.”

Situated just steps from the Bell Museum’s front entrance and adjacent to classrooms, the new Touch & See Lab is still home to old favorites—the deer skeleton, elephant skull and live animals, including snakes, box turtles, tarantulas, geckos and cockroaches. But many new hands-on adventures await too. Jennifer Menken, who has managed Touch & See since 1995, is particularly excited about the lab’s two microEYE Discovery microscopes.

Designed to be durable enough for public spaces, the microscopes can be easily zoomed and focused by people of all ages without assistance. “They were the very first thing I wanted for this room,” she says, explaining that visitors can more easily explore and appreciate the intricacies in a variety of species with the easy to use, high resolution imaging tool. Staff will also use the microscopes to lead activities such as helping people swab and examine cells from the inside of their cheeks.

A family uses digital microscopes in the new Touch & See Lab.

As always, there will be plenty of bones, rocks, antlers and other specimens to interact with around the lab. But for the first time, the majority of the items used by staff for school and public programs will be on display in Collections Cove. Nestled within the Touch & See Lab, Collections Cove holds upwards of 4,000 items that people can have a look at, from Minnesota golden gophers and African butterflies to giant pine cones, fossils, and NASA artifacts like Apollo astronaut gear. The room is modeled after the real-life collection rooms that house over one million of the Bell Museum’s scientific specimens—all of which are currently used by researchers at the U of M and beyond.

“To this day, people from other museums come through and say they just can’t believe we put out real stuff for people to touch,” Menken says. “But it’s more important to have objects out there for people to interact with than to lock them up in a cabinet. You learn more when you can engage all your senses.”

Touch, See, Learn

U of M science education professor Roger Johnson was recruited to help create a totally new museum experience with the original Touch & See in 1968. Fifty years later, he explored its much bigger successor with his grandchildren, who zinged around the lab…

Read more about Dr. Johnson’s visit to the new Touch & See.

Artfully curated

Touch & See has long been home to the Bell’s popular sketching program, now called After Hours. One night a month, the museum offers professional artists and enthusiasts alike the chance to study unique, often rare, specimens which are especially curated for the evening.

Touch & See Room in the 1970s.

Collections Cove invites visitors and K12 students alike to experience what a real natural history collection room is like.

Immersive learning at it's finest, Touch & See is about asking questions, observing, and handling specimens to further your appreciation for the natural world.

Aha moments happen regularly in Touch & See, no matter your age.

Live animals have also been an important fixture of the Touch & See experience.

UMN students who staff the Touch & See Lab are more than happy to answer questions, bring out live animals, and share their enthusiasm for nature...or put a cockroach on their head.