Tim Whitfeld, who joined the Bell team this summer, grew up in a rural area of Southern England. He spent his childhood hiking the footpaths that crisscross the countryside—and fishing. “I think being out in nature was what piqued my interest [in natural history]. I also read a lot of books that contained descriptions of British natural history,” he says.

Though he was interested in natural history, he didn’t realize then that it could be a job. Instead, he went on to complete an undergrad in agricultural economics, followed by an environmental internship in Ohio. “Then I was in Minnesota teaching classes about nature, so suddenly I needed to learn about nature,” he says.

He worked with teens, bringing them on trips to the Boundary Waters and helping them learn about plants. “That’s where I got hooked on understanding plants and trying to learn their names,” he recalls. Whitfeld moved on to a master’s degree focused on field biology, and worked for a while as a field botanist with the Illinois Natural History Survey, followed by a position at Harvard University Herbaria.

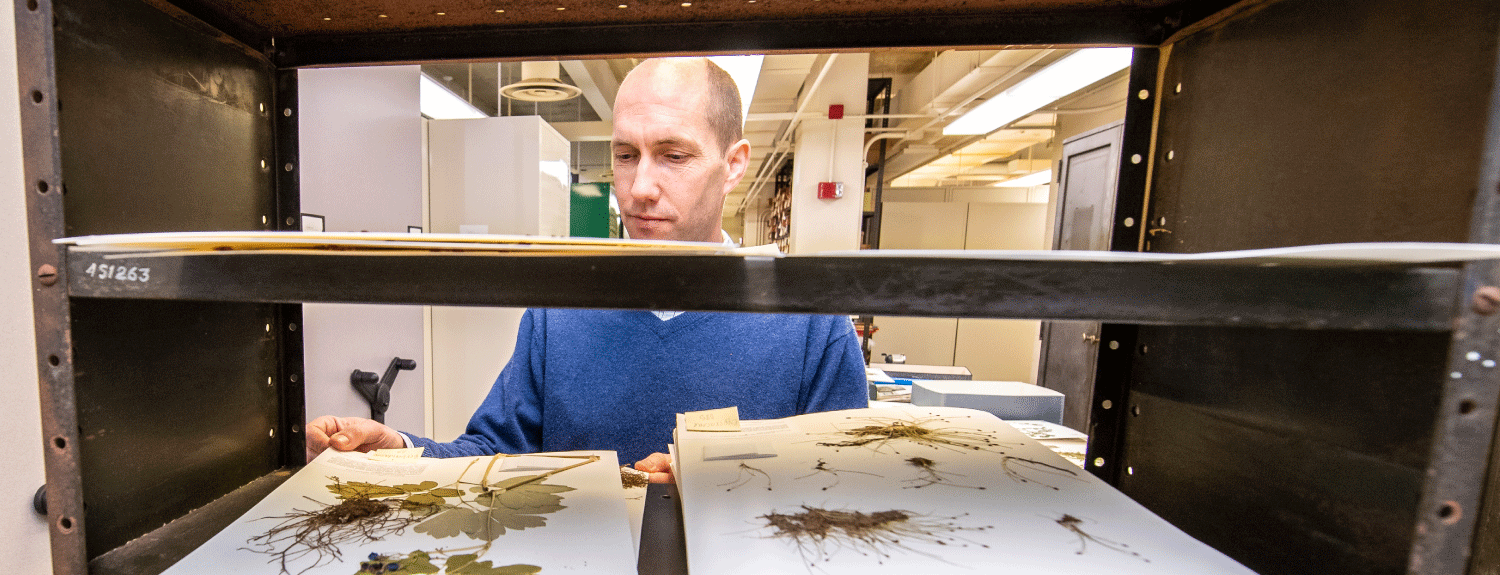

This huge collection of about five million specimens made Whitfeld realize that he wanted to be “someone who went out and collected plants,” and that he’d need a Ph.D. to do that. So after working as a field botanist with the DNR’s Minnesota Biological Survey, he came back to the University to study with George Weiblen at the College of Biological Sciences.

“At that point I was committed to this path of botanical research, botany, and ecology, did a postdoc in the Forest Resources Department with Peter Reich, an invasive species project, then took a job at Brown University as herbarium director.”

Plant Diversity Across Time & Space

Our plant collection is made up of more than 900,000 dried pressed plants from all over the world. Of these, 600,000 are vascular plants including flowering plants, conifers, and ferns; of those, 200,000 were collected in Minnesota. The collection comprises of fungi, lichens, mosses and algae, which are generally dried and mounted on a sheet like the other plant specimens. Each plant was collected in the field, going back to the early 1800s—collectors usually snipped a twig including leaves, flowers, and fruits, and pressed it between sheets of newspaper to dry a few days. In the case of small wildflowers, an entire plant including the roots is sometimes used for the specimen. The resulting two-dimensional specimen is glued onto archival quality cardstock and installed in the herbarium.

Whether the specimen is a part of the plant or the whole thing, the label is key: It lists the scientific name, location and date of collection, and sometimes details about the plant’s habitat and person who collected it.

The herbarium’s collection represents a botanical history of plant diversity through time and geographic space. In the past, scientists mainly used this resource to understand plant classification and identify plants collected in the field—it’s a very useful reference collection and source of information for classification. Some of the most valuable pieces are the type specimens, which are like a birth certificate for a new plant species. They are the basis for the written descriptions of new species and can be referenced when botanists want to understand the original “concept” for a particular species.

While documenting plant diversity and resources for plant classification were the original functions of herbaria, “natural history collections went out of fashion a bit during the mid 20th century, as scientists become more interested in molecular rather than organismal biology,” Whitfeld says. But as the effects of climate change started to become obvious, researchers realized the herbarium record provides a botanical history documenting environmental change through time. With over 350 million specimens contained in the 3,000 herbarium collections around the world, biologists have the information at their fingertips to track changing plant distribution and diversity.

“Ideally you’d have the time and money to go around the world and collect specimens,” Whitfeld says. “But with the herbarium you can take advantage of two hundred years of previous work for our studies of plant taxonomy and plant ecology.”

A record from the Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas of Cystopteris fragilis, or brittle bladder fern.

The Collection Has the Data

The herbarium’s collection is still important for taxonomy and understanding plant evolution. With modern DNA analysis, though, a complementary approach to classification emerged. Before, classification meant looking at plant morphology (leaves, flowers, fruits) and comparing those over different groups. If they look similar, there’s a good chance they’re related. This approach doesn’t always work, though—lots of things that were lumped together because of shared morphology turned out to have DNA that wasn’t so similar. Today’s DNA sequencing isn’t perfect, but it does often help clarify some of the relationships among plants, sometimes rewriting the evolutionary record of plants.

The University of Minnesota Herbarium is one of the largest in a public university, and has a very strong collection from the state that we’re in—200,000 specimens just from Minnesota, which gives a clear picture of local plant diversity. “I think the connection with the Bell is really exciting because we’re using the collection in a way that’s not just research. Education, interaction with the specimens for people who normally wouldn’t have contact with them: Outreach through museum is a unique and exciting aspect of this collection.”

Having a core collection from the state is extremely useful when it comes to understanding the plants we have here. A big part is thanks to the Minnesota DNR over the last 30 years or so, Whitfeld says, but we also have a lot of old specimens, too, so there’s a continuous record of plant diversity through time in the state. That’s not always the case: Lot of collections have a lull or gap in the timeline.

The collections also complement our dioramas. The dioramas are useful in understanding what an area looked like at a particular point in time, and you can go out now into the remnant patches and see what’s growing there, but the collection gives a big picture of what was growing in the Big Woods or the prairies over time—the collection has the data.

Collections as a Public Resource

The herbarium provides information about plant diversity in an area, giving context and data that helps conservation efforts. If you’re interested in restoring prairie on your land, it’s useful to know what had been there before development. In the same vein, lakeshore restoration is a popular project—people keen on planting native species to decrease erosion can use the collection to see what plants historically grew in the area.

Beyond that, botanical art and illustration are a common use of the collection; anyone interested in botanical art can take advantage of this great trove of specimens for inspiration.